I’ve been thinking more this week about a connection between our Sunday school lesson on early church persecution and Pastor Babij’s sermon on how The Gospel Makes All Things New. In Christ, people who normally would not have any reason to associate with each other but plenty of reason to hate one another find supernatural fellowship and love together. The gospel indeed totally transforms our relationships!

This is a reality that is not only true today but was also true in the early church. In fact, when we consider the first converts and martyrs, we see the wondrous unity in diversity that God designed to exist in his church, a unity which not only causes the members of the church to serve together but even to suffer and die together.

Something to know about the makeup of the Roman empire, and, thus, the makeup of the early church, is that the populace was quite ethnically diverse. To be Roman was not to be a white Italian or even a white European; the Roman Empire included people from the Middle East (Jews, Arabs, Palestinians, Syrians, Persians), Africa (Egyptians, Carthaginians, Mauritanians), the Mediterranean (Greeks, Illyrians, Italians, Iberians), Northwestern Europe (Celtish Gauls and Britons), and even places outside the empire from which people traveled or were taken as slaves (Germans, Nubians, Scythians, Indians).

And the people of these regions didn’t simply stay put within the empire; the prosperity and security of the empire encouraged travel so that there was a great mingling of ethnic backgrounds within the greater Greco-Roman culture. Thus, when the gospel came to different regions of the empire, and people believed, those persons brought their different backgrounds into the church, resulting in the situation Paul describes for the church in Colossians 3:11:

A rewewal in which there is no distinction between Greek [Gentile] and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave and freeman, but Christ is all, and in all.

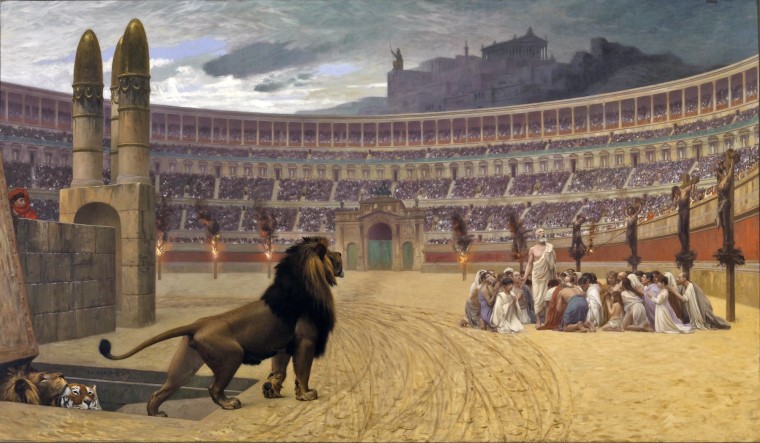

As violent persecution broke out against Christians at various times and places within the empire, Christians from each of the above ethnicities suffered and were even martyred.

But the diversity of the persecuted was not simply ethnic; when we study the martyrdom accounts left behind, we find out that Christian martyrs were both rich and poor, masters and slaves, old and young, men and women, educated and uneducated, pastors and laymen, new converts and seasoned saints. Even in the excerpt that we looked at from the Letter from Vienna and Lyons in Sunday school, we saw notable variety in the Lugdunum martyrs. Who was it that perished after suffering many tortures? Sanctus, a deacon from Vienna in the Alps; Maturus, a new convert; Attalus, a church leader from Pergamus—probably the city in Asia Minor; Blandina, an old slave-woman; Blandina’s mistress, left unnamed; and Ponticus, a fifteen-year-old boy. As these dear and diverse believers had lived together in Christ, they died together in Christ, with all outer distinctions fading away and their one bond and hope in the Lord shining through.

Today, as the people of our culture find more and more reasons to be suspicious of one another, to divide from one another, and even to hate one another, we Christians should be different. The gospel makes all things new in Christ. We do not regard people according to the flesh anymore, either in the church or outside the church (2 Cor 5:16-17). God has given us a glorious ministry of reconciliation (2 Cor 5:18-21). Let us pursue that ministry together, happy to suffer for Christ and both with and for one another.

Questions to Consider:

1. Do you regard others according to the flesh, leading to partiality? What would James say about that (James 2:1-12)?

2. People sometimes claim that Christianity is just a “white-man’s” religion or a European/Western religion. How do the Bible and early church history refute those claims?

3. How does love for your brethren translate into both tangible service and suffering?